For this blog, I wanted to explore PCOS and insulin resistance (IR). I was intrigued for a various set of reasons. I have a good friend with PCOS and may of the complications associated with it, including significant immune and metabolic issues. In addition, with launching of the weight loss app (Diet Achiever), I am certain there will be a good percentage of the folks who are struggling with their weight as a result of PCOS. This will be written in a blog format with the hopes of sharing this in the future.

What

is PCOS?

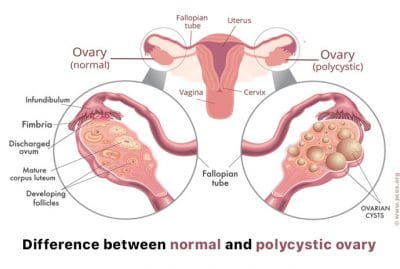

PCOS is a hormonal condition that is often associated with irregular menstrual

cycles, fertility difficulties, excess male hormone levels and small follicles

on the ovaries (Galan, 2019). Common

symptoms include weight gain (particularly around the belly), acne, hirsutism

(male pattern of facial hair), skin tags, and higher risk of miscarriage

(Glenville, 2012). Cysts are the classic

sign of PCOS. According to Glenville

(2012), to be diagnosed as PCOS 2 of the 3 criteria below have to be met:

- Infrequent or no ovulation

- Signs of hirsutism or acne or blood tests that indicate high male hormones

- Polycystic ovaries seen on ultrasound

Other characteristics include abnormal blood markers such as elevated LH, low FSH, elevated estrogen, low sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and elevated androgens (Glenville, 2012). Dyslipidemia is often common too, such as elevated triglycerides, cholesterol, and low HDL/LDL ratios (Marshall & Dunaif, 2012).

Additionally, many patients also have insulin resistance (IR), often seen with elevated fasting insulin and fasting glucose. In fact, the increased insulin promotes the liver to produce less SHBG, which lead to elevated estrogen and androgens. About 44-70% of women with PCOS also have IR, which can be a risk factor for pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and metabolic syndrome (Bailey et. al, 2019). Insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance are key drivers in the pathogenesis of PCOS. The hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, an increased oxidative stress all contribute to the onset of this condition (Bailey et al, 2019). “In fact, insulin resistance may actually be the root of one’s PCOS, playing a role in causing the condition in the first place, as well as exacerbating its symptoms” (Galan, 2019). Elevated insulin levels may also be a contributing factor to inflammation and other metabolic complications associated with PCOS. Inflammation can impair insulin action and glucose tolerance, and could be one of the links between hyperandrogenism, IR and abdominal obesity with PCOS (Bailey et al, 2012). This is often seen with elevated inflammatory markers such as CRP, IL-6, WBC, and TNF-a. Some experts suggest that the obesity associated with IR may promote the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to produce excessive androgens that then lead to PCOS. Other risk factors associated with the IR include depression, infertility and miscarriage (Galan, 2019).

Although hyperinsulinemia is common in PCOS, it is

unclear if this is due to excessive insulin secretion or decreased insulin

clearance or both (Phy et al., 2015).

“Persistently elevated

insulin levels, immaterial of its origin, can result in insensitivity of its

target cells over time, which further exacerbates hyperinsulinemia and

increases the potential for beta cell dysfunction” (Phy et al., 2015). Individuals with IR have a reduced ability to

oxidize fatty acids because of elevated insulin levels, leading to tissue

accumulation of triglycerides in skeletal muscle and further impaired insulin

signaling. The elevated insulin then

decreases expression of LPL (lipoprotein lipase) in skeletal muscle and increases

expression in fat cells, which drives lipolysis in the adipocyte, leading to

higher levels of circulating fatty acids that further impair insulin signaling

and lipid oxidation in skeletal muscle, leading to more weight gain and further

metabolic dysfunction (Phy et al., 2015). It appears to be the perfect storm.

Screening for PCOS would include testing the bloodwork for some of the abnormalities listed above. However, according to Bailey at al (2012), post-prandial dysglycemia are often more prevalent than fasting glucose in PCOS as compared diabetes. It may be a good idea to ask the physician to run an oral glucose tolerance test, as it is believed to be more relevant in terms of identifying risk for developing prediabetes or T2D in women with PCOS (Bailey et al, 2012).

What can be done?

According to Marshall and Dunaif (2012), all women with PCOS should be treated for IR (Marshall & Dunaif, 2012). Options for treating IR include lifestyle modifications, exercise, dieting and weight loss or targeted medications or supplementation. “. Given the high prevalence of obesity in women with PCOS, efforts to achieve weight reduction are an important component of treatment of the disorder” (Marshall & Dunaif, 2012). Weight loss alone has been, when undertaken with diet and exercise interventions, have been shown to reduce hyperandrogenism, increase ovulation, and improve metabolic function.

Because women with PCOS are naturally more insulin resistant, it makes losing weight and maintaining a healthy BMI more challenging. Activities that raise blood sugar should be avoided. These include living a sedentary lifestyle, eating a diet high in refined sugars and carbohydrates, and leading a high stressful lifestyle. In addition, using products with endocrine disrupting chemicals such as BPA and parabens should be avoided, as they interfere with the body’s ability to regulate hormones and can add fuel to the fire.

Dietary Strategy

The dietary strategy I have seen in literature that works best is a low glycemic, lower carbohydrate diet. Although many places are promoting a ketogenic diet, I am not convinced that this is the right approach. I have blogged about this in the past, but in a nutshell, literature indicates that a high fat diet can be problematic in context of intestinal permeability. The macronutrient ratio of a true ketogenic diet is typically 70-80 fat, 20-25% protein and 5-10% carbohydrates. A high fat diet can be problematic if the patient also has leaky gut. This is due to saturated fat’s link to endotoxemia, which can contribute to low grade inflammation which can dysregulate the “inflammatory tone” and contribute to hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and whole body, liver and adipose tissue weight gain! (That sounds a bit like the characteristics of PCOS)! The more endotoxins create more inflammation, more inflammation and insulin resistance, and immune dysregulation (High Intensity Health, 2017). LPS can bind to receptors of many cell types, but particularly has an affinity for monocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells (Fulop, 2018). As I said in my previous blog, the problem is not the fat per se, but the type of fat. In 2013, Mani et al demonstrated that meals rich in saturated fat such as coconut oil can increase postprandial endotoxin level concentrations, while meals high in omega-3 PUFA fish oil lowered endotoxins. According to a few studies I read, oils rich in DHA and EPA (fish oil, cod liver oil, algae oil) can attenuate LPS transport, while oils higher in saturated fats (coconut oil, palm oil, animal fats) can increase transport. In addition, a ketogenic diet is a difficult diet to adhere to long term and often results in lack of compliance. In addition, a true ketogenic diet would consist of 30g of total carbohydrates or less, and would typically be low in fiber. Since dietary fiber consists of prebiotics essential for a healthy microbiome, I am really cautious when advising on ketogenic dieting. It also may not be necessary to go that extreme with PCOS.

Patients with IR can benefit from a low insulin promoting diet without having to go full ketogenic. Studies have shown that diet-induced hyperinsulinemia via the consumption of a high glycemic/high insulinemic diet promotes obesity, insulin resistance, increased carbohydrate cravings and decreased fat utilization. Total carbohydrate intake of 100g per day can safely improve insulin resistance without contributing to some of the complications that may occur with a true ketogenic diet. In fact, a study in 2015 indicated that a diet of low starch/dairy can result in successful treatment of obesity and co-morbidities linked to PCOS. The study demonstrated that an 8-week low starch/low dairy diet resulted in weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced free and total testosterone in women with PCOS. These were just the results of dietary interventions alone without exercise! The women in the current study showed a significant reduction in body weight, body fat percentage and waist circumference, which could be attributed to the relatively low energy and/or carbohydrate intake. (Phy et al., 2015).

A low insulin promoting diet would be high in fiber and low in simple sugars and starch/dairy. High fiber foods can be beneficial for satiety, motility and also contains polyphenols that are important for cell to cell communication. Aim for about 30g of fiber per day.

The best fiber sources for low insulin PCOS diets include:

- Avocado

- Cauliflower

- Broccoli

- Brussels sprouts

- Asparagus

- Bell peppers

- Chia seeds

- Flax seeds

- Dark, leafy greens (like kale, arugula and spinach)

Lignans are also a type of fiber that may lower androgens and insulin levels while boosting SHBG which are needed to help clear some of the excess estrogen and androgens associated with PCOS. Things such as flax seeds, sesame seeds, berries and broccoli.

Dr. Glenville gave some good dietary strategies that can be considered:

- Inclusion of omega-3 fatty acids- as EPA and DHA have demonstrated to show increase in cell membrane responsiveness to insulin. In addition, omega-3 fats are anti-inflammatory driven and can inhibit inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-a. However, some omega-6 in the form of ghee is helpful for the production of butyrate for optimal GI function, so careful balance of omega 3 and omega 6 should be planned in the intervention

- Avoid dairy due to its insulin promoting effects

- Cut out alcohol as it impairs phase 1 and phase 2 liver detoxification pathways, needed to metabolize estrogen and testosterone

- Reduce or avoid caffeine due to its cortisol promoting effects

- Supplement

with vitamins and minerals (if deficient) (Glenville, 2012)

- Chromium- improves insulin sensitivity

- Magnesium- magnesium deficiency is linked to IR

- Vitamin D- deficiency can be associated with inflammation and IR.

- Vitamin E- can improve insulin sensitivity via improving membrane fluidity of cell membranes.

- Vitamin C- can improve fat metabolism during exercise (up to 300%) and also acts as a potent antioxidant. Vitamin C deficiency can also trigger higher levels of cortisol.

- Zinc- can help the body cope with stress and appetite.

- Alpha lipoic acid- contributes to improved insulin sensitivity but also is a pretty good heavy metal chelator

- B vitamins- are required for energy production and the ability to cope with stress.

- Amino acids- BCAA’s can help counteract high levels of cortisol and blood sugar, arginine helps with stress responses, carnitine is involved in fat burning and energy production, NAC improves insulin sensitivity and is a precursor to glutathione (antioxidant), glutamine is needed when under stress and also can nourish the intestinal epithelial cells and tyrosine can suppress appetite and burn fat.

Finally I wanted to mention the use of inositol that a classmate brought to my attention. Myo (MI) and D-chiro-inositol (DCI), the most studied inositol isoforms, are classified as insulin sensitizers. In form of glycans, DCI-phosphoglycan and MI-phosphoglycan control key enzymes were involved in glucose and lipid metabolism (Lagana et al, 2016). Considering the key role played by insulin-resistance and androgen excess in PCOS patients, the insulin-sensitizing effects of both MI and DCI were tested in order to ameliorate symptoms and signs of this syndrome, including the possibility to restore patients’ fertility. Interestingly, both isoforms of inositol are effective in improving ovarian function and metabolism in patients with PCOS, although MI showed the most marked effect on the metabolic profile, whereas DCI reduced hyperandrogenism better. “Consistent with these findings, restoring inositols levels with oral supplementations ameliorates insulin-resistance, hyperandrogenism, regularity of menstrual cycles, and oocyte quality in patients with PCOS (Lagana et al, 2016). The authors of the study propose a “tailored” dosage, based on the pretreatment conditions, which may allow clinicians to improve the current knowledge about long-term outcomes in this population.

Exercise

As a fitness instructor, I cannot forget about exercise. Exercise has multiple benefits from physiological changes to improvement in moods. Exercise also has a strong influence on the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Gleeson et al., 2011). In fact, there is a strong relationship to BMI that may indicate that the decrease in inflammatory molecules may be related to decrease in visceral fat. Additionally, physical activity may further mitigate inflammation by improving endothelial function, increasing insulin sensitivity, enhancing liver health and increasing blood vessel growth and blood flow.

There are many types of exercise protocols/prescriptions. The one that I use often is called Metabolic Training. It consists of steady state cardio (typically in aerobic or dance format) with some weight training in either Tabata or some type of timed format. I typically use Rest-Based Training (RBT), which has become popular through one of my mentors Jade Teta. His philosophy is to “push till you can’t, rest till you can”. According to Teta (2017):

RBT is a system that makes rest, not work, the primary goal of the workout. It allows participants to take a rest for as long as necessary. Rest actually becomes a tool for increasing intensity, because exercisers can strategically use it to work harder than they could without rest. It also provides a buffer against overexertion, making even high-intensity workouts safe. In RBT, the protocol adapts to the individual rather than forcing the individual to adjust to it. I have found this style of exercise has been the most beneficial to improve insulin sensitivity, increase lean body mass, and improve neurological function as well. Compared to a sedentary lifestyle, aerobic exercise had the greatest effect on AHN (adult hippocampal neurogenesis), and high intensity interval training promotes neuroplasticity (Nokia et al., 2016). Conducting the exercise on an empty stomach either after an overnight fast or 3-4 hours after a meal may improve insulin sensitivity.

Intermittent Fasting

I also wanted to mention, although it was not in the literature presented in this module, but intermittent fasting (IF) may be a good intervention for IR (Arnason, Bowen, & Mansell, 2017). In an interesting pilot study in 2017 demonstrated that short term, daily IF may be a safe and tolerable intervention that may improve key outcomes including body weight, fasting glucose and postprandial variability in glucose. The IF that was discussed in this pilot study involved limiting food intake into a single 4 to 8h period daily, or fasting for 16 to 20 hours. This may need to be implemented in phases to prevent reactive hypoglycemia, so starting with a 12-hour fast is best, followed by adding 1 hour intervals of fasting periodically within the comfort level of the person. Another strategy I have used myself is to fast for 20-24 hours one day weach week and fast 12 hours on the other days. So essentially, I only eat 6 days per week. I have also conducted a full 5 and 8-day water fast that had many interesting health outcomes, but I will save that for another blog!

Another style of fasting I thought was interesting for people with adrenal dysfunction is “Bulletproof intermittent fasting”. It involves using Bulletproof coffee beans in the morning with either grass-fed butter or Brain Octane oil for breakfast, no carbs or protein. You can consume this several times until you break the fast, as it will not promote insulin secretion while still getting fasting benefits without the downsides of fasting. I would recommend sticking to decaf coffee since caffeine can sometimes be hard on the adrenals.

Here is the recipe for the Bullet Proof Coffee that can consumed during fasting

To learn more about healing form IC naturally, please visit our website: http://ichealer.com If you are looking for self healing, we recently launched our Self Healing IC Course featuring 10 hours of video designed to help you discover your root cause. Once you know your root cause, you can start your healing journey. To find out more information about our exciting new course, please find the information below:

Here is the link to preview the course: http://ichealer.com/online-course/

Here is the Podia Course Page: https://ichealer.podia.com/course

The first module is totally FREE. You have nothing to lose and everything to gain. For more insightful videos on these burning topics, simply subscribe to this page so you can be notified of up to date information.

Join us on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/IC-Healer-103255207780907/

Instagram https://www.instagram.com/ichealerofficial/

Twitter https://twitter.com/ic_healer

References

Arnason, T. G., Bowen, M. W., & Mansell, K. D. (2017). Effects of intermittent fasting on health markers in those with type 2 diabetes: A pilot study. World J Diabetes, 8(4), 154-164. doi:10.4239/wjd.v8.i4.154

Bailey, B; Phinney, S, Volek, J. (2019). Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, Insulin Resistance and Inflammation. Retrieved (2019, February 2) from https://blog.virtahealth.com/pcos-polycystic-ovarian-syndrome/

Fulop, J. (2018). High-Saturated Fat Increases Endotoxemia. Retrieved (2018, November 24) from https://www.naturalmedicinejournal.com/journal/2018-07/high-saturated-fat-diet-increases-endotoxemia High Intensity Health (2017). Gut Health & Keto Diets- Endotoxemia and Bacterial Diversity w/ Tommy Wood, MD PhD. Retrieved (2018, November 24) from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_K2pmc4SKCU

Gleeson, M., Bishop, N. C., Stensel, D. J., Lindley, M. R., Mastana, S. S., & Nimmo, M. A. (2011). The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol, 11(9), 607-615. doi:10.1038/nri3041

Lagana, A. S., Rossetti, P., Buscema, M., La Vignera, S., Condorelli, R. A., Gullo, G., . . . Triolo, O. (2016). Metabolism and Ovarian Function in PCOS Women: A Therapeutic Approach with Inositols. Int J Endocrinol, 2016, 6306410. doi:10.1155/2016/6306410

Marshall, J. C., & Dunaif, A. (2012). Should all women with PCOS be treated for insulin resistance? Fertil Steril, 97(1), 18-22. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.036

Phy, J. L., Pohlmeier, A. M., Cooper, J. A., Watkins, P., Spallholz, J., Harris, K. S., . . . Boylan, M. (2015). Low Starch/Low Dairy Diet Results in Successful Treatment of Obesity and Co-Morbidities Linked to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). J Obes Weight Loss Ther, 5(2). doi:10.4172/2165-7904.1000259

Sperlazza, C. (n.d.) Reverse Insulin Resistance with Intermittent Fasting. Retrieved (2019, February 11) from https://blog.bulletproof.com/insulin-resistance/

Teta, J. (2011). Rest-Based Training. Retrieved (2018, October 8) from http://www.ideafit.com/fitness-library/rest-based-training